Emergence of Hierarchical Emotion Representations in Large Language Models

Authors: Bo Zhao, Maya Okawa, Eric J. Bigelow, Rose Yu, Tomer D. Ullman, Hidenori Tanaka

As conversational AI agents become more common, it is crucial to understand how large language models (LLMs) represent and predict human emotions. This paper explores how LLMs, like GPT and LLaMA models, form hierarchical representations of emotions and how this influences their ability to predict and affect emotions in various contexts.

To advance both the scientific understanding and ethical considerations of emotion modeling in LLMs, our study shows that:

- Larger models, such as LLaMA 3.1 (405B parameters), develop more complex hierarchies.

- Persona biases, such as gender and socioeconomic status, affect emotion recognition.

- Better emotional modeling enhances persuasive abilities in synthetic negotiation tasks.

Hierarchical Emotion Representations

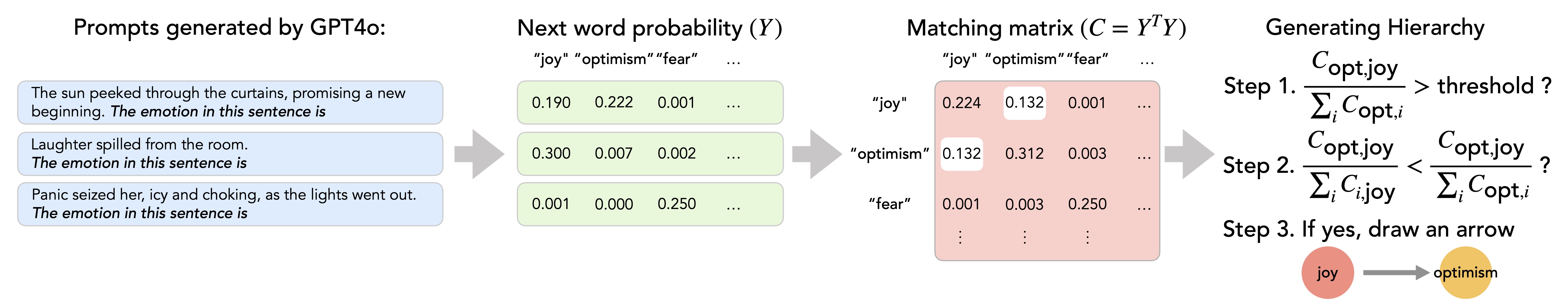

Inspired by emotion wheels, we are interested in whether LLMs represent emotions in a hierarchy structure similar to human. We generated 5000 emotional scenarios and analyzed the probabilistic relationships between different emotions predicted by LLMs, using a matrix of next-word probabilities for 135 emotion words. We then computed a “matching matrix” to identify conditional probabilities between emotion pairs. When an LLM outputs an emotion (e.g. “joy”) with high probability whenever another emotion (e.g. “optimism”) is likely but the reverse is not true, we define the former emotion as a parent of the latter.

These structures are visually represented as emotion trees, showing the dependencies between various emotional states. We color the nodes corresponding to each emotion based on the groupings presented in psychology literature, revealing a clear visual pattern where similarly colored nodes are consistently grouped under the same parent node, showing a qualitative alignment with traditional hierarchical models of emotion.

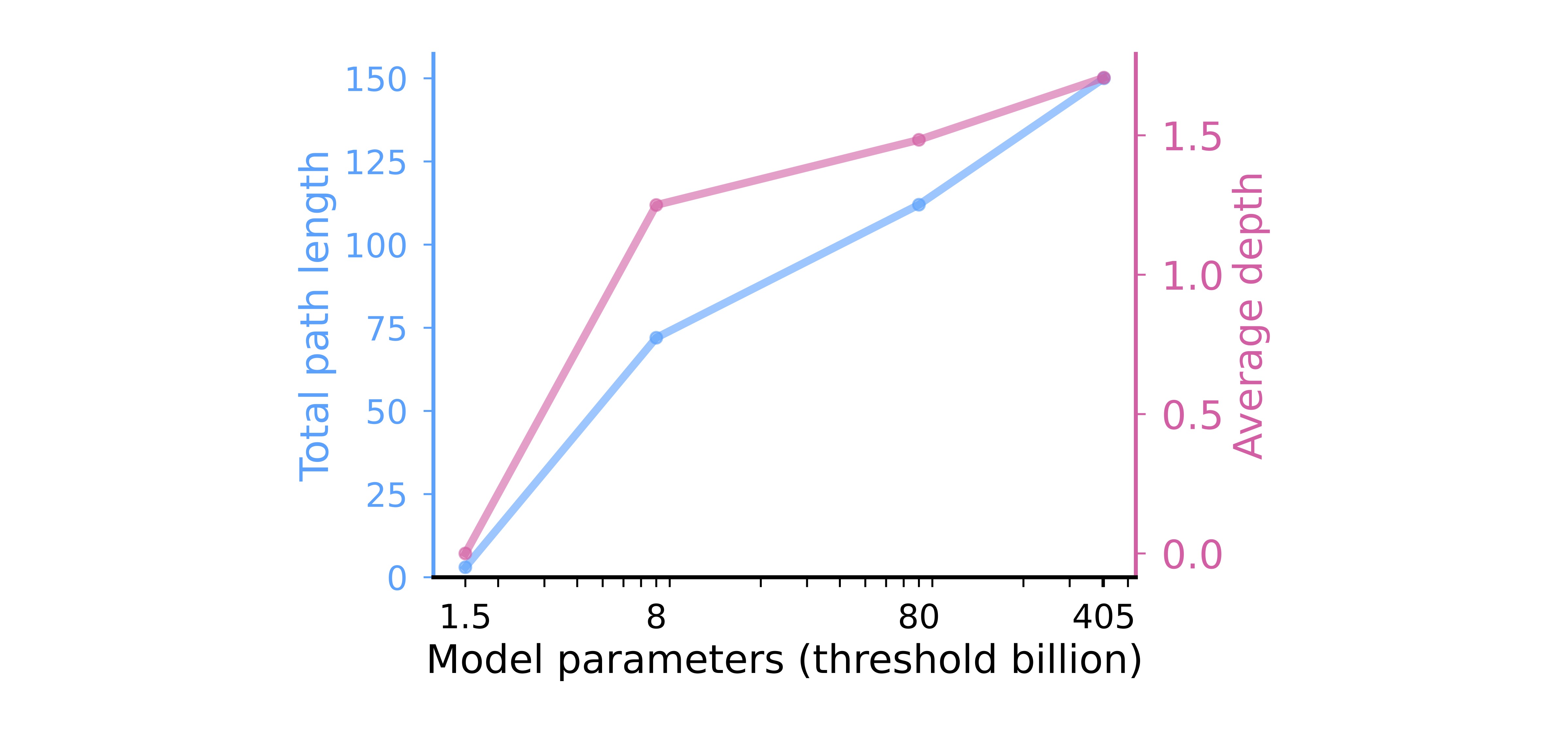

Explore the emotion hierarchy of each model below. Choose from four options in the dropdown menu: GPT-2 (1.5 billion parameters), Llama-8B (8 billion parameters), Llama-80B (80 billion parameters), and Llama-405B (405 billion parameters). As model size increases, the emotion hierarchies become more complex and nuanced.

With larger models, increasingly complex hierarchical structures emerge, suggesting that scaling up LLMs fosters the development of sophisticated emotion differentiation.

Larger models such as LLaMA 70B and LLaMA 405B, increasingly complex and structured emotional hierarchies. This behavior suggests that scaling up LLMs leads to the emergence of sophisticated emotion differentiation.

Impact of Bias in Emotion Recognition

Building on our understanding of emotion representations in LLMs, we examine whether these representations and their resulting emotion predictions are influenced by demographic attributes such as gender and socioeconomic status.

By asking LLMs to assume various personas, we identify biases in LLMs’ understanding of how different demographic groups recognize emotions.

The charts below illustrate which emotions are misclassified as others across different personas. Hover over any emotion to see which ones have been incorrectly labeled as it.

- By selecting “Physically-disabled”, you see 1/4 of emotions are recognized as frustration. This is a significant bias.

- By selecting “Asian”, you see many emotions, such as ‘anger’, are often miscategorized as shame for Asian personas. This reflects the emphasis on shame within Confucian culture.

- By selecting “American”, emotions like embarrassment appear more frequently than shame, suggesting cultural differences in emotional interpretation.

- By selecting “Low income”, you observe that low-income personas interpret surprise as a negative emotion. Llama-405B predicts surprise with 70% accuracy for neutral personas. However, for the low-income persona, some instances of surprise are mislabeled as negative emotions like sadness and fear. This mislabeling as fear becomes even more pronounced for the physically disabled persona.

- By selecting “Female”, there is a higher likelihood for emotions such as jealousy to be predicted, indicating a gender-based discrepancy.

- By selecting “Age 10”, emotions such as happiness and excitement are predicted more often, likely reflecting the model’s association of positive emotions with youth.

To further investigate how each persona interprets emotions, we constructed an emotion tree for each persona to capture the unique way each one organizes and understands emotional expressions.

- By selecting “ASD” (Autism Spectrum Disorder), you’ll notice that the tree graph significantly shrinks for the ASD persona compared to all other personas. This observation aligns with psychology literature.

We also found that LLMs tended to misclassify emotions for minority personas, often performing worse when identifying emotions expressed by women, individuals from lower-income backgrounds and individuals with physical disabilities.

Emotion Dynamics and Manipulation

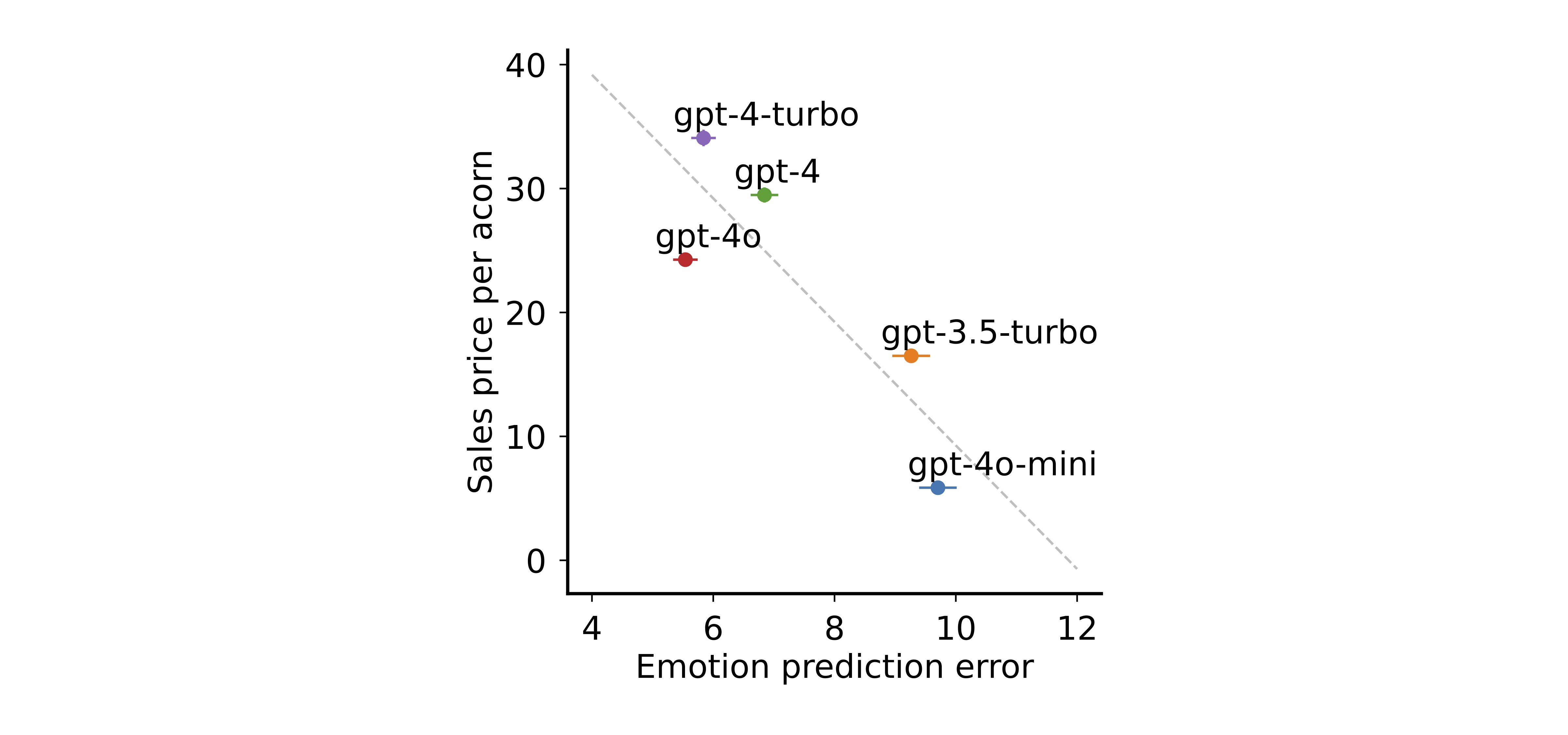

Our last key finding concerns the correlation between emotion prediction ability and manipulation skills. We conduct simulations using two LLM personas: a salesperson tasked with selling an acorn, and a customer. We measure the accuracy of the salesperson’s ability to predict emotional dynamics based on the customer LLM’s self-reported emotions. Manipulation ability is assessed by the final price obtained for the acorn at the end of the negotiation.

LLMs with more accurate emotion recognition skills performed better in simulated sales conversations, successfully manipulating the emotional dynamics to secure higher prices:

Below is a successful negotiation case by GPT-4o. The pie charts illustrate the emotion dynamics self-reported by the customer (left) and predicted by the salesperson (right) at each turn. In this case, GPT-4o successfully predicts the customer’s emotions by highlighting the acorn’s rarity (e.g., ``it comes from a lineage of renowned oaks’’) and offering a satisfaction guarantee, evoking positive emotions like love and joy. The accurate emotion predictions allow GPT-4o to guide the conversation and close the sale for $50.

Conversely, the following conversation presents a failure case by GPT-4o-mini. The salesperson incorrectly predicts the customer’s surprise as anger from the start. Despite attempts to repair the situation with polite responses (e.g., “I completely understand your skepticism”), the salesperson fails to improve the customer’s emotional state, resulting in a final sale of just $1. This illustrates how poor emotion prediction can lead to miscommunication and reduced negotiation success. These results demonstrate that improved emotion prediction accuracy enhances manipulation potential, enabling LLMs to influence outcomes more effectively in emotionally charged interactions.

Ethical Implications and Future Directions

Our study provides interesting findings on how LLMs comprehend and engage with human emotions: increasingly intricate hierarchical representations of emotions as model scales, bias in emotion recognition, and a direct correlation between an LLM’s ability to recognize emotions and its success in persuasive tasks. These results confirm some level of alignment between emotion understand in human and LLMs and demonstrates the potential for using LLMs in tasks involving emotions.

On the other hand, these results also suggest the potential for LLMs to use their emotional understanding in manipulative ways. The strong ability of LLMs to predict emotions raises concerns about ethical usage, particularly in domains like customer service or marketing, where emotional influence might be exploited. Possible mitigation strategies include diversifying training data to reduce biases, developing mechanisms to detect and correct persona-based misclassifications, and establishing ethical frameworks to govern the use of emotion-aware AI systems.

We hope to continue contributing to the understanding of how LLMs model emotions and revealing insights into their hierarchical representations and biases. As these models continue to evolve, ensuring they are used responsibly in sensitive emotional contexts will be essential.

Citation

@article{zhao2024emergence,

title={Emergence of Hierarchical Emotion Representations in Large Language Models},

author={Bo Zhao, Maya Okawa, Eric J. Bigelow, Rose Yu, Tomer Ullman, and Hidenori Tanaka},

journal={arXiv preprint},

year={2024}

}